Implementation of anxiety evaluation systems in laboratory mice using digital image processing

Main Article Content

Abstract

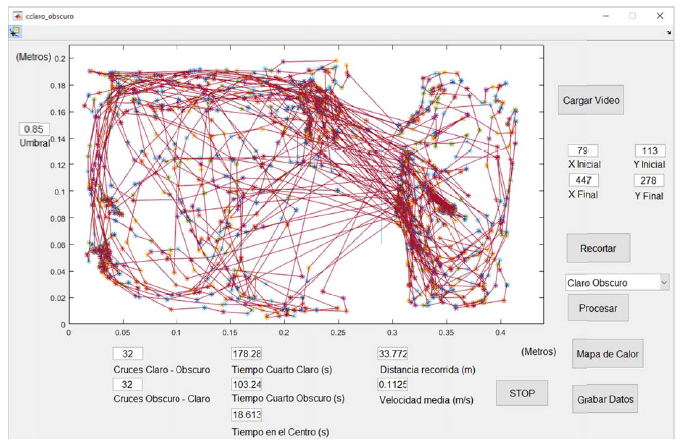

Currently, there are several techniques to evaluate anxiolytic behavior in laboratory animals since their behavior is very similar to that of humans. Such techniques include manual and observational methods, where the evaluator must carefully observe the entire experiment and document each of the events of interest made by the mouse or acquire electronic equipment that fulfills this function. However, the last option could be expensive. This article proposes the design and implementation of two low-cost anxiety assessment devices (Elevated Plus Maze and Light-Dark Box) using digital image processing, which, after the validation of the operation, delivers results automatically through an application developed in Matlab. The results provided by the application coincide with those that an observer would obtain manually and visually, facilitating the tasks of the evaluator and reducing the possible human errors and ambiguity existing in manual tests.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish in this journal agree to the following terms: Authors retain the copyright and guarantee the journal the right to be the first publication of the work, as well as, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others share the work with an acknowledgment of the authorship of the work and the initial publication in this journal. Authors may separately establish additional agreements for the non-exclusive distribution of the version of the work published in the journal (for example, placing it in an institutional repository or publishing it in a book), with acknowledgment of its initial publication in this journal. Authors are allowed and encouraged to disseminate their work electronically (for example, in institutional repositories or on their own website) before and during the submission process, as it may lead to productive exchanges as well as further citation earliest and oldest of published works.

How to Cite

References

[2] Cruz-Morales, S. E.; González-Reyes, M. R.; Gómez-Romero, J. & Arriaga, J. C. “Modelos de Ansiedad. Revista Mexicana de Análisis de la conducta, 28(1), 93-105. 2003.

[3] Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE & Briley M. “Validation of open: closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat”. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 14: 149-167. 1985.

[4] Becerra-García, A. M., Madelena, A. C., Estanislau, C., Rodríguez-Rico, J. L., Dias, H. “Ansiedad y miedo: su valor adaptativo y mal adaptaciones”. Revista Latinoamericana de psicología, 39(1), 75-81. 2007.

[5] Hogg S. A. “Review of the validity and variability of the elevated plus-maze as an animal model of anxiety”. Pharmacology Biochemistry Behavior, 54(1), 21-30. 1996.

[6] Rodgers, R. J., Cao, B. J., Dalvi, A., & Holmes, A. “Animal models of anxiety: an ethological perspective”. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research, 30, 289-304. (1997a).

[7] Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE & Briley M. “Validation of open: closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat”. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 14: 149-167. 1985.

[8] Lister RG. “The use of a plus-maze to measure anxiety in the Mouse”. Psychopharmacology, 92: 180-185. 1987.

[9] Rex A, Fink H & Marsden CA. “Effects of BOC-CCK-4 and L 365,260 on cortical 5-HT release in guinea-pigs on exposure to the elevated plus-maze”. Neuropharmacology, 33: 559-565. 1994.

[10] Hendrie CA, Eilam D & Weiss SM. “Effects of diazepam and buspirone in two models of anxiety in wild voles (Microtus socialis)”, Journal of Psychopharmacology, Abstract Book, A46, 181, 1994.

[11] Yannielli PC, Kanterewicz BI & Cardinali D. “Daily rhythms in spontaneous and diazepam-induced anxiolysis in Syrian hamsters”. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 54: 651-656. 1996.

[12] Crawley JN, Goodwin FK. “Preliminary report of a simple animal behavior for the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines”. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1980;13:167-70.

[13] Pavlov, I. P. “Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex” (G. V. Anrep, Trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1927.

[14] Randich, A., & LoLordo, V. M. “Associative and nonassociative theories of the UCS preexposure phenomenon: implications for pavlovian conditioning”. Psychological, Bulletin, 86 (3), 523-548. 1979.

[15] Fanselow MS, DeCola JP, & Young SL. “Mechanisms responsible for reduced contextual conditioning with massed unsignaled unconditional stimuli”. Journal of experimental psychology, 19(2):121–137, 1993.

[16] Zettlex [Online:] [Consulta: 27 de Abril de 2018]. Disponible en: https://www.zettlex.com/es/articles/sensores-de-posicion/

[17] Sense, Sensors & Instruments. “Sensores Ultrasónicos” [Online:] [Consulta: 27 de Abril de 2018]. Disponible en: http://www.sense.com.br/arquivos/produtos/arq3/Flyer%20US1300_Rev.%20D_Esp.pdf

[18] Losada C., Mazo M., Palazuelos S., Pizarro D., Marrón M., “Posicionamiento 3D de robots moviles en una espacio inteligente mediante camaras fijas”, XVIII Seminario Anual de Automática y Electrónica Industrial (SAAEI 2011), 2011, pp. 783-788.

[19] BORRE, Kai and STRANG, Gilbert. 2012. Algorithms for Global Positioning. Wellesley : Wellesley-Cambridge Press, 2012

[20] Universidad Técnica de Machala [Online:] [Consulta: 27 de Abril de 2018]. Disponible en : https://www.utmachala.edu.ec/